The year is 1766. Pune, the seat of the mighty Maratha Confederacy, is recovering from the scars of war—specifically, the devastating attack by the Nizam's forces just three years prior in 1763 which damaged the sacred Devdeveshwar Temple on Parvati Hill. It was here, in the shadow of this destruction, that Raghunath Rao, the younger brother of the great Peshwa Balaji Baji Rao (Nana Saheb I), decided to rebuild and expand. But amidst the temple dedicated to the presiding deity, Raghunath Rao made a choice that defies modern regional myths.

Sometime before embarking on a perilous campaign—the Maratha-Mysore War of 1767 against the formidable forces of Hyder Ali—the warrior-statesman knelt not only to Shiva and Parvati, but specifically to the war-god, Karthikeya (Muruga). In that newly built shrine on Parvati Hill, the Peshwa's kin sought the blessings of the valiant commander of the celestial armies, a deity often strictly labeled as a "Tamil God." This singular, powerful act of devotion, set right in the heart of the Maratha Empire, is where our journey begins to understand the truly Bharathiyan nature of Lord Muruga.

I, along with Mr. Jataayu went on an unplanned journey to this temple at Parvata Hill in Pune, thanks to the Chat GPT Suggestion and the cab driver who accompanied us. The cab driver mentioned that it has been so long he lives in pune and had never visited this temple. The visit uncovered to us that the identity of Muruga as the supreme God of War, or Deva Senapati, is not a regional development but a fundamental doctrine articulated in ancient pan-Indian literature. Many kings who happened to rule Bharat at various times, even further later in history, continued to worship Lord Muruga before they marched their armies into war.

The Skanda Purana, arguably the largest of the Mahapuranas, is entirely dedicated to his life and exploits, detailing his birth from Shiva's fiery seed and his immediate command of the celestial army. Crucially, the Mahabharata (Vana Parva and Shalya Parva) describes him as the son of Agni and Ganga (the divine spark from shiva’s third eye and savarana poigai), and the killer of the Asura Tarakasura, stating he "excelled by his heroism" and that he "was created for the destruction of the enemies of the gods."

Furthermore, the Ramayana mentions his birth as the commander destined to conquer evil. Even Kalidasa’s celebrated epic poem, the Kumārasambhava (The Birth of the War God), is dedicated to the circumstances leading to his birth and his subsequent victory over Tarakasura. These diverse texts consistently establish his role as Senānī (Army Commander) and confirm that his primary function is to embody courage, strategic warfare, and the defense of Dharma. The worship Raghunath Rao performed in Pune was, therefore, an acknowledgment of this ancient, subcontinent-wide textual tradition of Kartikeya, the powerful general.

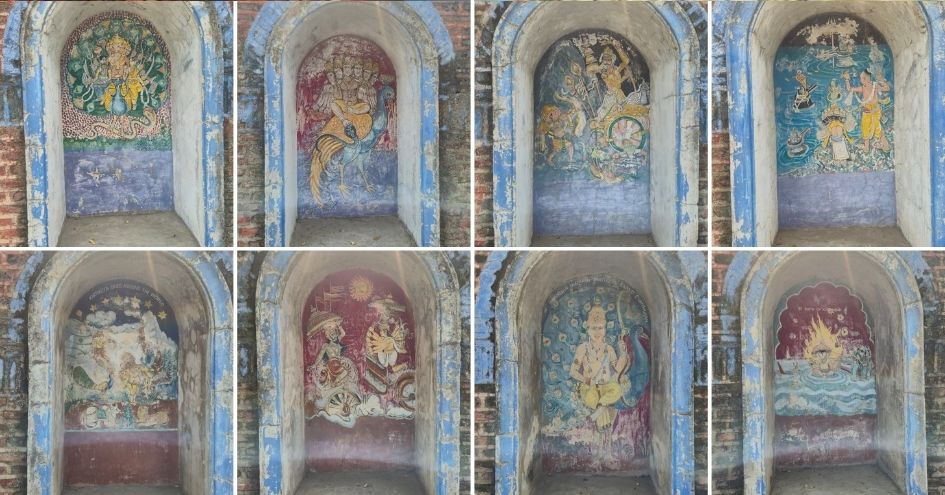

The history connecting a Peshwa-era warrior, Raghunath Rao, to the temple's war-god is compelling, but the one thing that truly solidified the pan-Indian reality of Muruga was the vivid iconography decorating the shrine’s exterior walls. Though likely added or refurbished in a later period, these paintings visually narrate the quintessential tales of the deity, bridging geographical distance with shared ideology.

Adorning the walls are detailed depictions of the birth of Lord Muruga/Kartikeya, showcasing his divine origins from Shiva and the six Krittikas. More strikingly, the mural cycle includes the infamous Gnyana Pazham (Fruit of Knowledge) story, where Muruga, upon being denied the prized fruit, famously leaves Mount Kailash to reside on the hills of the South—the very story that defines his relationship with his devotee bases in Tamil Nadu. The victorious climax is also represented: the fierce battle and eventual defeat of the Asura Surapadman.

These painted narratives are not merely decorations; they are documented evidence that the stories defining Muruga's identity, often considered the exclusive cultural property of the South, were actively known, appreciated, and visually immortalized right here in the heart of Pune, Maharashtra.

If the historical context places Muruga in Pune, and the murals narrate his popular stories, then the central image of the deity—the murti itself—is phenomenal. The idol housed in the Parvati Hill shrine is striking: it is a beautiful representation of Shanmukha (the six-faced one), standing or seated, clothed in vibrant yellow fabric. Crucially, the idol distinctly displays six heads mounted on its vahana, the peacock.

This six-faced form, while central to his identity as Kartikeya/Shanmukha in Sanskrit Puranic literature, is surprisingly unique as the primary worship idol in many temples of the South has the peacock on the outside of shrine, though found in mounted form in sculptures a lot. This Pune murti, displaying the six heads and his mount, emphasizes the Northern and Western reverence for him as Kartikeya—the son raised by the six Krittikas. The idol demonstrates a deliberate choice to venerate Lord Muruga in a form that resonates deeply with the broader, ancient Bharathiyan tradition, underscoring the unifying identity of the War God from Maharashtra to Tamil Nadu.

Elsewhere within the temple complex, we discovered a second white marble murti of the deity, reinforcing the fact that the devotion here was neither singular nor accidental. Adding compelling historical weight is a partially damaged idol, likely a precursor or victim of war, housed within the Nana Saheb Peshwa Museum located inside the same compound.

This broken piece—perhaps damaged during the Nizam's assault in 1763 or left uninstalled (unknown)—further corroborates the temple's enduring connection to Lord Kartikeya. It could be the reason why the wooden plaque outside the temple says the re-established date as 1799. While photography restrictions prevented documentation of this museum artifact, its very presence serves as a silent testament to the deity’s importance in this Maratha power center. [Note: I urge all readers visiting Pune to witness this historical continuity firsthand by visiting the museum on Parvati Hill.] These multiple representations—two idols and a museum artifact—speak volumes about the lasting, legitimate devotion to the God of War in the heart of Maharashtra.

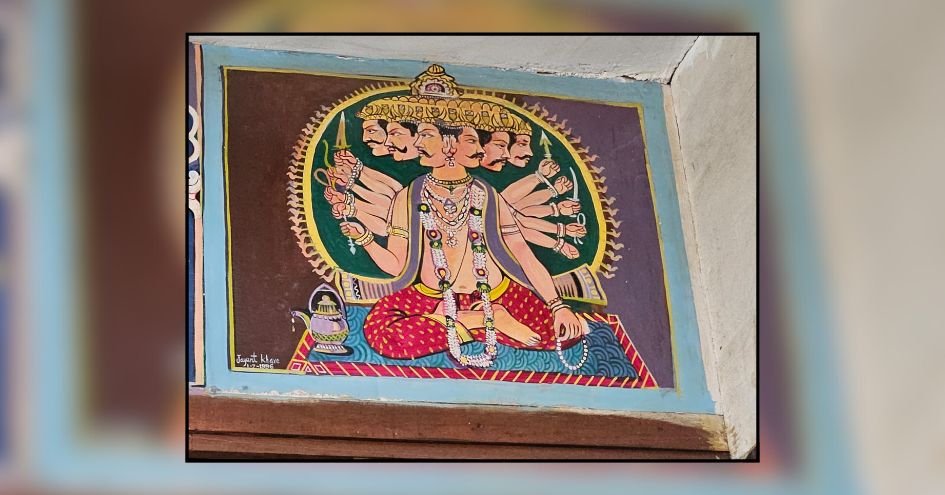

The most intimate evidence of how the Peshwas integrated the God of War into their own cultural fabric lies within a specific painting found in the Nana Saheb Museum, drawn later in 1996. This artwork depicts the six-faced Shanmukha in an astonishingly localized form: sporting a valiant Indian swirl moustache. Such a depiction is incredibly rare, almost unseen in the traditional iconography of South Indian temples. This visualization suggests the Peshwas did not merely adopt a deity; they personalized him, envisioning Muruga not as a distant southern figure, but as one of their own—a courageous Maratha warrior ready for battle.

This cultural assimilation is further cemented by other idols in the complex, including the Shiv Linga, which is ritually adorned with a Pheta (a traditional Maratha turban). This practice is a powerful testament to the deeply personal and organic nature of faith across Bharat, where devotees saw the divine not as an untouchable foreign entity, but as a beloved, accessible member of their community, complete with local attire and features. It perfectly illustrates how religion always had regional threads of perceptions, which are misused by the separatist forces to weave myths around them.

The remarkable discovery on Pune’s Parvati Hill—a Muruga shrine consecrated by the Peshwa's family before a major war, adorned with murals of Tamil lore, and housing an iconic Shanmukha idol—offers an undeniable answer to our central question. Lord Muruga, or Kartikeya, is not merely a regional deity of Tamil Nadu. He is, and always has been, a Bharathiyan God.

The ancient Puranic texts established his role as the Deva Senapati long before state borders were drawn, and the Peshwas, through their personalization of him with a swirl moustache and Pheta, demonstrated that the divine is universally adopted and loved across the subcontinent. The seamless integration of Muruga's history, iconography, and mythology into the Maratha heartland is a powerful rebuttal to any myth of religious separation.

This temple stands as a testament to the essential truth: the faith of India is an intricate, unified web of truth, where regional differences are merely vibrant threads woven together by a shared, timeless devotion. The warrior god who commands the celestial army is, truly, the beloved son of all of Bharat.

Vigneshwaran, Senior Correspondent of TheVerandahClub.com is both a skilled digital content writer, story teller, marketer, acupuncturist, as well as an avid independent writer driven by his passion. His literary talents extend to crafting beautiful poems and captivating short stories including the Sehwag Tales series. In addition to these creative pursuits, he has also authored a book titled "Halahala," which can be found on Wattpad.

Vigneshwaran, Senior Correspondent of TheVerandahClub.com is both a skilled digital content writer, story teller, marketer, acupuncturist, as well as an avid independent writer driven by his passion. His literary talents extend to crafting beautiful poems and captivating short stories including the Sehwag Tales series. In addition to these creative pursuits, he has also authored a book titled "Halahala," which can be found on Wattpad.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

In the lush, green heart of Kerala lived an elephant who became a living legend - a tale of an elephant turned into a bakth. His name was Keshavan, bu...

The Chaitanya Charitamrita by Shri Krishna Das Kaviraj provides a vivid description of the operations management of Shri Gundicha Yatra during the tim...

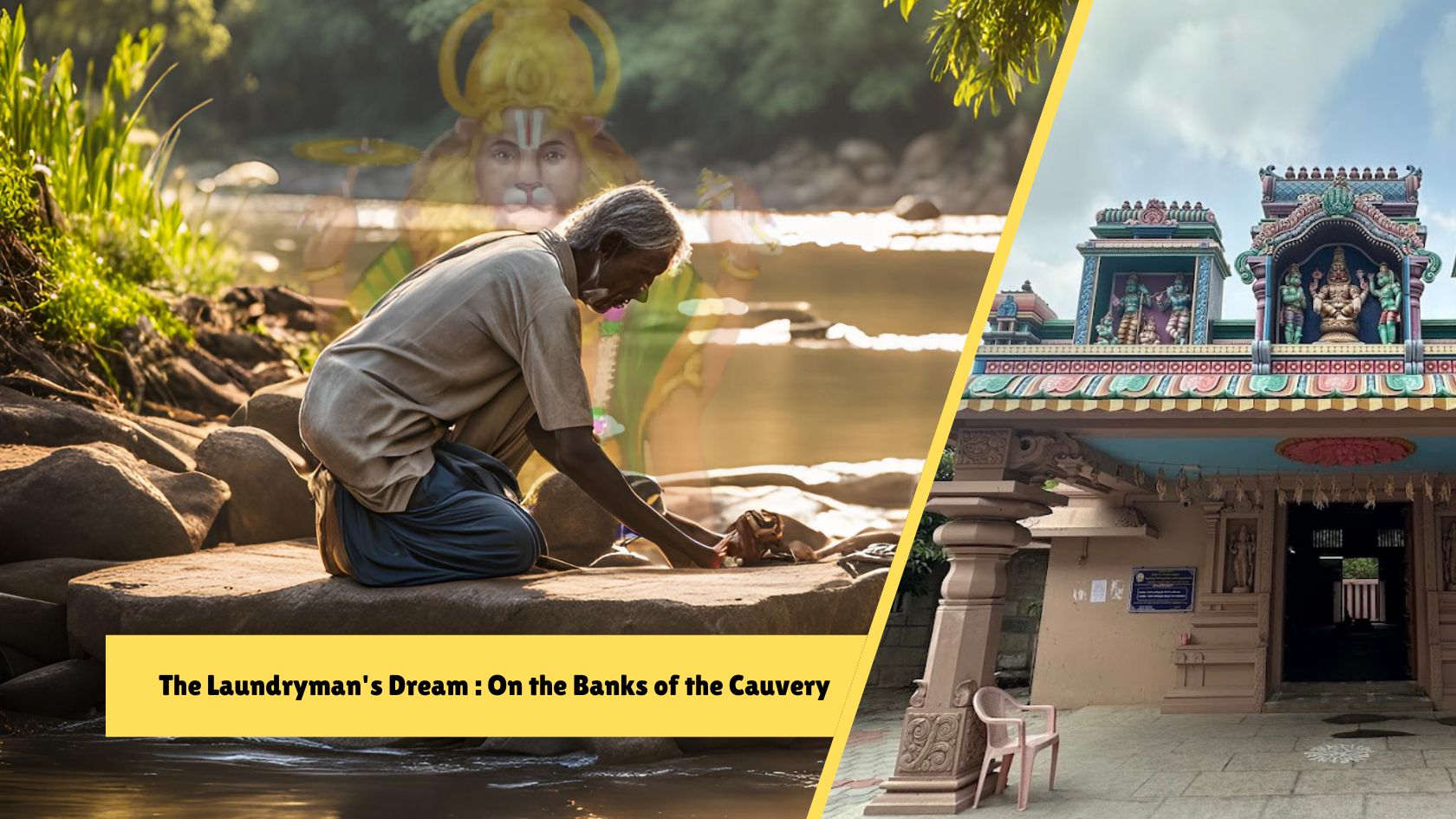

The sun beat down on my back as we stepped out of the car, the air thick with the humidity of rural Tamil Nadu. Chinthalavadi, a small village nestled...