The Sengol has become a popular subject of discussion thanks to the central government’s decision to install it during the inauguration of the Parliament building on the 28th of May. There has been a lot of excitement ever since the government announced its decision. Most people have welcomed the move since it brings out an iconic symbol from our past. There are, of course, naysayers with many objections. Many others are confused since they don’t know about the Sengol and its significance in the history and culture of Bharatavarsha. It is appropriate to know more about the Sengol and what it means to Bharatiyas.

What is the Sengol?

The Sengol is a symbol of power and is also referred to as a sceptre or a ceremonial rod that signifies power and authority. It is derived from the Tamil words Semmai and Kol, Semmai meaning dharma or righteousness, and kol referring to stick. While the term is Tamil in meaning, the concept of the Sengol is not restricted to Tamil Nadu, but is a concept that has been prevalent in India for ages.

So, why is the Sengol being spoken about today? What is its significance now? As we all know, a new Parliament building is being inaugurated on Sunday, the 28th of May. The earlier Parliament was built during the British Raj and is an old building. The new building aligns with the aspirations of new India and can house more Parliamentarians.

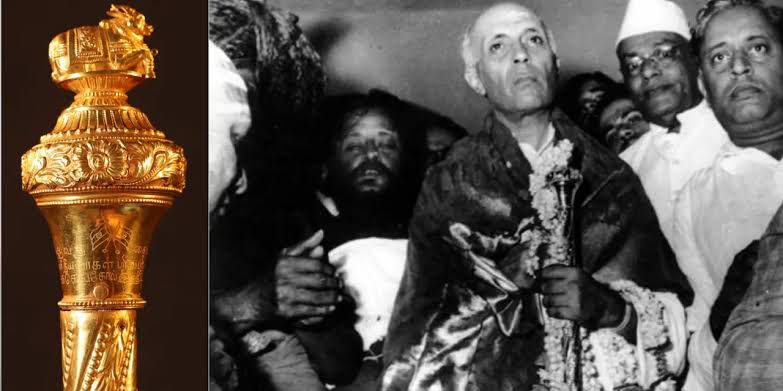

An interesting fact that has come out today that most people were not aware of is that the Sengol was given to Pandit Nehru in 1947. When India became a free country, the British left India, handing over power to an Indian government headed by Jawaharlal Nehru. The transfer of power happened symbolically with the handing over of the Sengol.

Origin of the Sengol

When the transfer of power took place, there was a discussion on how to do it symbolically. C Rajagopalachari (who would become Governor General of India after Mountbatten) suggested the Sengol be used for the ceremonial transfer of power. Rajaji contacted the pontiff of the Tiruvadutharai Adheenam (a Shaiva matha in Tamil Nadu). They decide to follow the tradition of the Sengol that was once used by the Cholas and Cheras.

The pontiff was not keeping well, and he assigned the job to his deputy. The Swami got the Sengol from well-known Vummidi Bangaru Chetty jewelers. The Sengol was made from wood and then gold-plated. It was a 5-foot long rod with the Nandi bull (Shiva’s vehicle) on top of it. The time taken to craft the Sengol was 30 days with 8 people working on it. The cost at that time was 15,000 – a significant amount.

The deputy pontiff Kumaraswamy Thambiram handed the Sengol to Mountbatten, took it back from him, purified it, and then gave it to Nehru. When Nehru took the Sengol in his hands, it signified the formal transfer of power from the British under Mountbatten to a free India led by Nehru. The Sengol represented the sceptre of power that kings of ancient times wielded.

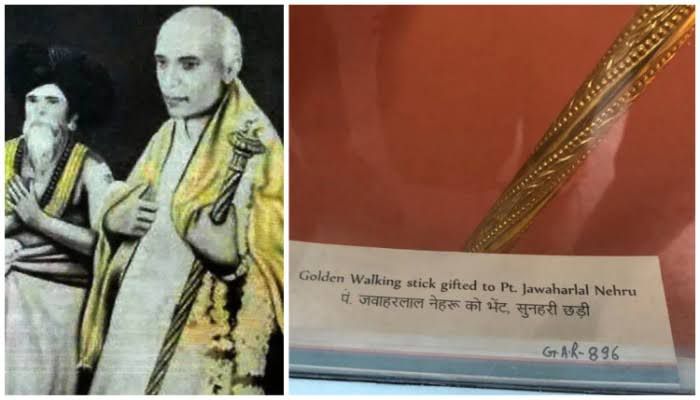

So, what happened to the Sengol after this event? The Sengol was not retained by the then PM but moved to Anand Bhavan where a museum was established later. Interestingly, the museum has a description stating that it was ‘a golden walking stick’.

Eminent danseuse Padma Subramaniam wrote to the PM in 2021 highlighting the need to bring back the Sengol. The government accepted this suggestion and has now decided to install the Sengol near the Speaker’s chair in the new Parliament.

The importance of the Sengol or the Raja Danda

The sceptre is a term familiar in the histories of other cultures. Kings in almost all countries held a sceptre in their hand as a symbol of power. Was the sceptre used in our country? The answer to this question is a resounding yes! We have the concept of raja danda or the ceremonial staff used by the king.

Chanakya refers to the Danda Niti, which is the power of the king to chastise or punish people who do wrong. The king’s duty or dharma is to use his powers to help the good and punish the evil. The concept of danda is that the king uses his power (as the wielder of the sceptre) to punish wrongdoers.

In fact, Chanakya states that Danda Niti enables the king to rule over his kingdom effectively and do justice to all his subjects. Danda Niti stresses the use of power and force to ensure control over the subjects by the king. Regulation is needed for an orderly society and this is where the danda niti helps. The king wields his power and ensures people follow rules so there is peace and stability.

While Chanakya’s Danda Niti is well-known, he was not the first to talk about this concept. Manu introduces the concept of Danda niti to discipline people and punish the evil. Manu says that the king has to protect his subjects and he can do this by using the danda. Manu and others later were clear that the danda should be used judiciously.

There is extensive reference to the danda in the Mahabharata. It is said that there is nothing in the world that is not there in the Mahabharata. So, if we are talking about the Sengol, then there must be some reference to it in the Mahabharata. We can find this reference in the Bheeshma Parva.

Danda in the Mahabharata

After the Kurukshetra War, a dejected Yudhishtira wanted to abdicate and renounce the world. Bheeshma, lying on the bed of arrows awaiting the right moment to leave his world, then advises Yudhishtira. During the extensive dialog between the two, Bheeshma advises Yudhishtira to follow dandaniti. Bheeshma says that the king who follows Dandaniti ensures peace.

Bheeshma then explains the origin of the danda niti and danda in detail. In ancient times, the danda or rod of Brahma disappeared when he was busy in a sacrifice. As a result, there was chaos in the world. No one respected the others, and the strong oppressed the weak. Brahma then prayed to Mahadeva Shiva.

Shiva then created the danda from his own self. He then gave the rod to Vishnu, who handed it over to the sage Angiras. The sage then gave it to Indra from whom it reached Marichi and then went to Bhrigu. From Bhrigu, the rod went to Kshupa and finally reached Manu. The rod was then transferred by Manu to his sons who ruled the earth.

Since then, the danda has been an integral part of every kingdom. The danda is held by the king as a symbol of his power and authority. It must be noted that danda means staff or sceptre. It also means punishment. The danda signifies the king’s power to punish the evil and protect the good.

The danda is thus a concept that dates back thousands of years and originates from Shiva himself. This explains why the Sengol was designed with Nandi on it. The Cholas followed the tradition of the Sengol when they ruled the land of the Tamils. It is not that other kings did not use the danda, but the Sengol came into prominence thanks to Rajaji’s suggestion to Nehru.

In ancient times, the sceptre or danda was handed over by the rajaguru or royal priest/preceptor to the king. The tradition was followed by many of the kings who came later. Even in other countries, the king would hold the sceptre, and this tradition was followed during the coronation of King Charles of UK.

Sengol in today’s India

In our country, our quest to become ‘secular’ led to ancient traditions being abandoned. It is heartening to note that the traditions of the old will be revived on the 28th May 2023 with the installation of the Sengol. We are today not a monarchy but a proud democracy. In a democracy, the Prime Minister is the ruler, and it is apt that he receives the danda or Sengol in a traditional way.

In democracies, power rests with Parliament elected by the people of the country. The decision of the government to install the Sengol in Parliament is a praiseworthy one. Whenever our rulers and representatives see the Sengol near the speaker’s chair, they will (hopefully) remember its tradition. It would remind them that they hold great power, and it is their duty to wield this power for the people – to protect the good, punish the evil, and ensure peace.

Deepak M R is a professional writer and author, who has previously worked in academics, training, and consulting. He is the author of the novel ‘Abhimanyu – the warrior prince’ (Bloomsbury, 2021). He is also a contributing author in the anthology Unsung Valour (Bloomsbury, 2020) and a KDP e-book ‘Mahabharata Tales: Justice for Draupadi and other stories’. He is an avid fan of Hindi film music.

NEXT ARTICLE

Indian History is rife with conflict between kings for power, territory and regional supremacy. We have seen instances where kings have made it a poin...

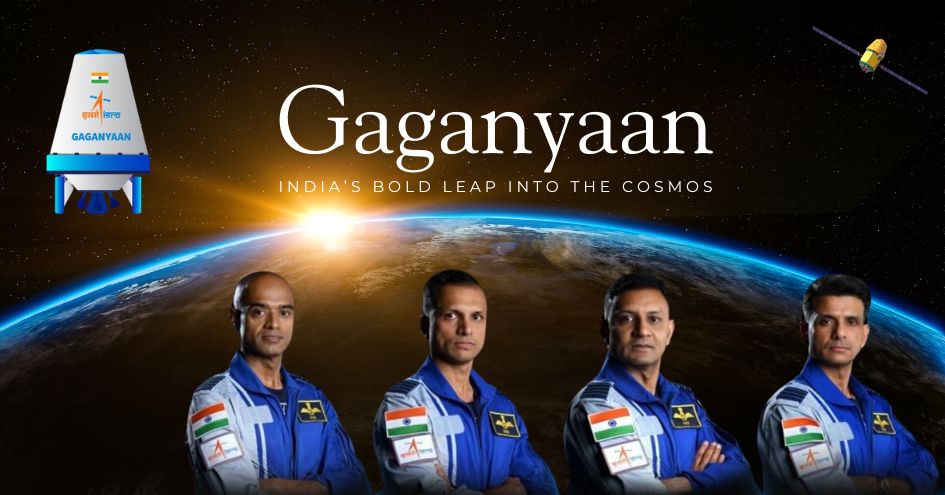

"Saare Jahaan Se Accha, Hindustan Hamara!"These immortal words, spoken by Squadron Leader Rakesh Sharma from the vast expanse of space in 1984, When t...

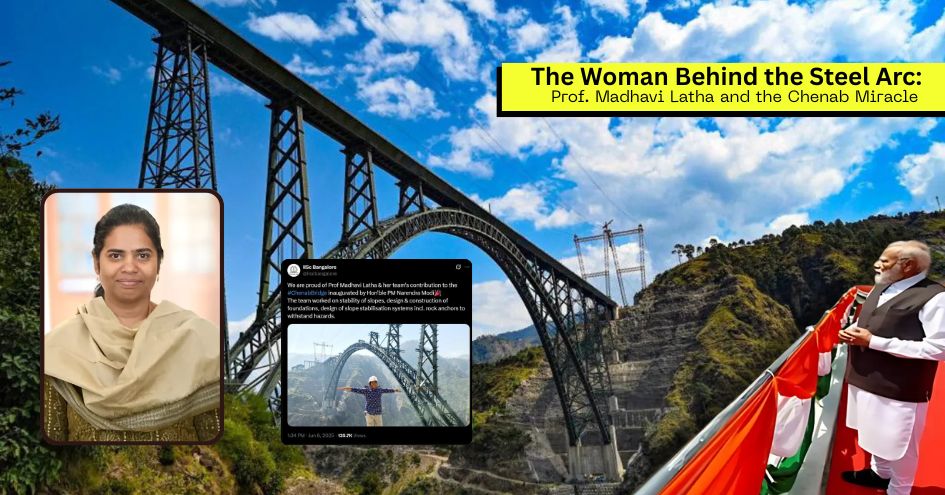

High in the rugged, unforgiving terrain of Jammu and Kashmir’s Reasi district, where the Chenab River slices through deep gorges and the Himalayas loo...