The 19th century has just dawned. British power is now slowly consolidating its footprint across the subcontinent – it will soon spawn a rule that would soon span nearly one and a half century. But life in India is full of perils. Apart from threats posed by wild animals and insects, diseases run rampant. One of the most virulent of diseases was the smallpox – which on average killed 10% of the world’s population in those times – with the figure rising to near 20% in densely populated towns. But on this front, a breakthrough had been made as the previous century was ending.

Edward Jenner, an English doctor, developed a vaccine for smallpox. The British crown immediately took it up to introduce inoculation across its territories worldwide. India was no exception. The objectives weren’t entirely altruistic. The vaccine program was also intended to demonstrate to the “natives” the superiority of the white man and hence why their rule was to be welcomed. Also, protecting people from the scourge of this deadly disease was also a way to win the gratitude of the Indian subjects.

But rolling it out on ground in the subcontinent was not easy. The common Indian had no major reason to trust the British colonizer. Moreover, to an early 18th century Indian, the concept of vaccine was quite alien they were extremely reluctant to volunteer for the process. The British plans for mass inoculation looked to be in dire straits. Just at that point of time, up stepped a lady from a royal family whose story has been largely obfuscated by the winds of time.

After the fall of Tipu Sultan in 1799, the British East India Co. reinstated the Wadiyar dynasty to the throne of Mysore with the 5-year old Krishnaraja Wadiyar III becoming king in June, 1799. Around 1805-6, Krishnaraja was married to Devajammani – both being around 12 years of age at the time. And it was the young chief queen who would now take a leading role to set a precedent for her countrymen.

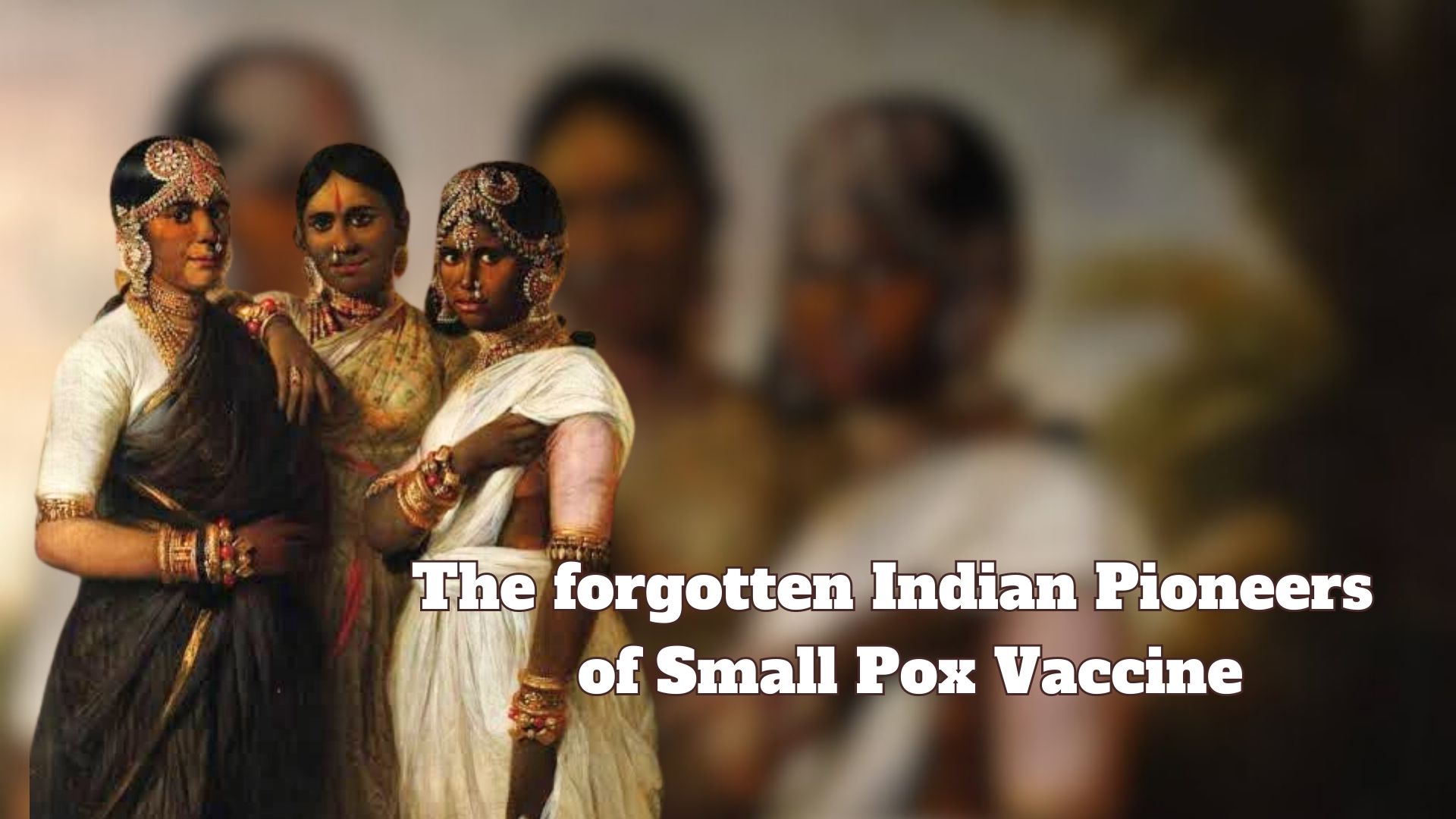

The Company administration resorted to many means to drive the adoption of vaccine by the Indians. One of these was endorsement by Indian native rulers – held in high esteem by their subjects and more importantly, trusted much more than the colonizers from distant lands. The royal family of Mysore took up this initiative whole heartedly and actively. An evidence of this lived on in a painting commissioned by the Company at the time to provide impetus to the inoculation campaign. It showed three Indian women, heavily decked in jewelries with the lady on the right pointing to her left arm – where she’d been inoculated.

For a long time, the three women were considered as courtesans or dance girls from royal courts. But only recently, historian Nigel Chancellor has refuted this view and instead, has used visual clues from the painting to theorize that the three women were from the Mysore royal family and the one used as the principal model was none other than the young queen Devajammani.

It was a courageous step for these royal women, whose exact identity may well prove to establish inconclusively. From volunteering for the vaccine – still a rather unknown commodity – to posing for the painting, it went far beyond the usual call of duty of a royal personage. But the Wadiyar royal family of Mysore had always proved to be exceptional in this sense – caring deeply for the land and their subjects. And thanks to this portrait, a slice of history is preserved showing their deep sense of duty and devotion to the motherland.

Based out of Kolkata, Trinanjan is a market researcher by profession with a keen interest in Indian history. Of particular interest to him is the history of Kolkata and the Bengal region. He loves to write about his passion on his blog and also on social media handles.

Based out of Kolkata, Trinanjan is a market researcher by profession with a keen interest in Indian history. Of particular interest to him is the history of Kolkata and the Bengal region. He loves to write about his passion on his blog and also on social media handles.

NEXT ARTICLE

"A staggering one in five children in India is pre-diabetic," revealed Mrs. Swathy Rohit, the visionary founder of Coimbatore-based digital health p...

Where a rhythmic cadence of music blends seamlessly with the structured world of auditing, we found Mukund Swaminathan, a 26-year-old maestro who has...

"Life doesn't offer retirement, only professions do. While I've stepped away from my practice, I haven't retired from living. No one truly retires whi...