A Kaleidoscopic View of Bharatanatyam

Dance was one of the ‘Ṣodaśa Upacāra-s’ (16 important offerings) and it was considered very important from time immemorial. Ādavallān or expert dancer has been one of the forms of Śiva, Naṭarāja – the King of Dance. The Ḍamarū (‘Udukkai’ in Tamil) found in the hands of Lord Naṭarāja created sound waves, and this resulted in the birth of music. It is from music that dance was born. Eventually, the grammar of dance became essential for performing arts and this led to the birth of drama.

Bharatanāṭyaṃ is amongst the ancient dance forms of India and was born in the Tañjāvur region of Tamil Nadu. This sacred dance was formatted and eventually offered as worship to Lord Naṭarāja. Every dancer experiences sublime height of emotion through his/her movements. He/She leads his/her audience into the state of divine consciousness. The Magnum Opus, ‘Sivagamiyin Sapatham,’ by Kalki extends this refinement into our minds at the climax when Sivagami performs in front of Lord Ekāmbareśvara at Kanchipuram.

This offspring of Tañjāvur was also known as ‘Sadhir’ and it was a reserve of the Devadāsī community. All the three, dance, drama, and music, were always offered to the divine. Social issues and gender issues were always part of ancient and medieval sacred compositions. Therefore, they were addressed through performing arts for centuries. Bharatanāṭyaṃ is much more than the movement of limbs, for even the motion of a little finger and a glance of eyes becomes very important.

The dance postures had been formalized long ago and a committed artist can possibly use her entire being in order to make the audience understand the emotions well. ‘Navarasa’ or Nine emotions are also known as ‘Rasā-s’ in Indian aesthetics. The song, ‘Maraindhu Irundhu Paarkum Marmam Yenna’ in the movie, ‘Thillana Mohanambal’ shows Padmini displaying all the nine of them – Śṛṅgāra (Love), Hāsya (Mirth), Vīra (Heroism), Raudra (Anger), Bhayānaka (Terror), Bībhatsa (Disgust), Adbhuta (Wonder), Karuṇa (Compassion) and Śānta (Tranquility). According to Bharata’s ‘Nāṭyaśāstra’ and ‘Tolkāppiyaṃ’ one can only go into 8 Rasā-s, for Śānta Rasa was introduced by Udbhaṭa in the 9th century.

Nṛtya and Nāṭya are the two primary elements of dance. While Nāṭya is the dramatic part, Nṛtya is rhythmical and repetitive movements of the 32 body parts of the dancers. In Nāṭya, one can see dramatic art in the form of Abhinaya and Mudrā. It is in Nāṭya that one poses with the aid of the limbs. Abhinaya consists of facial expressions that can display several emotions. The Mudrā is done with the help of fingers and hands in order to express the attributes of Gods or to identify the animals which are in the composition. However, both Abhinaya and Mudrā can be enjoyed by the viewers only if they are found in a small group.

‘Silappadikāraṃ’ belongs to the Saṅgaṃ age and has dancers like Mādhvī as important characters. The Beautiful Mādhvī who gave birth to Maṇimegalai was able to perform 11 types of dances. Movies like ‘Vanji Kottai Vaalibhan’ show dance contest in their full grandeur. The song, ‘Kannum Kannum Kalandhu Sonndham Kondadudhe’ is a masterpiece. Both Padmini and Vyjayanthi Mala had performed extremely well. Kumari Kamala one more of the famous dancers who did both teaching and dancing. Queens like Śāntalā, the spouse of Hoysala ruler, Viṣṇu Vardhana, were known to perform Pūjā in front of the deities found in temples.

The twentieth century saw the advent of institutions like Kalakshetra and pioneers like Rukmini Devi Arundale, brought them out of the exclusive preserves of the Devadāsī-s. Several great dancers were created, and it was left to eminent critics like Subbudu to throw light on their performances. It was during the time of the Cholas that position of the dancer became hereditary and new dancers could break the cordon only through the display of their fabulous talents. These dancers known as Devaradiyār-s used to dance in Śiva temples and the Yemberumānar Adiyār-s danced in Vaishnavite temples. Temple's dancers followed Sanskrit text and Kūtthu-s continued to be important. They were part of important festivals.

The ‘Kūthanūl’ by Sāṭṭanār was written in the 12th century and it talks about several aspects connected with dance. Ancient texts tell us about several forms of Kūtthu – Kuravai Kūtthu, Aka Kūtthu, Kura Kūtthu, Vethiyal, Thudi Kūtthu, Malladal, Śānti Kūtthu, and Podhuviyal. The Kūtthu-s brought out the close connection between dance and drama. A drama consisted of units of dance set to music. It was during the later medieval period that the Sanskrit Nāṭyaśāstra and Kūtthu became compartmentalized.

It becomes important to understand works like ‘Kūthanūl’ by Sāṭṭanār. ‘Suvai Nūl’ talks about various aspects of dance. ‘Togai Nūl’ describes dance forms which include the 108 postures or Tāndavā-s. Eminent danseuse, Padma Subramaniam has done a lot of research in this regard. ‘Vari Nūl’ is on folk dances and it includes Agavari (Love and Psychology), Kuravari (Natural phenomena) and Mugavari (Extraordinary movements). ‘Vāchai Nūl’ is on ludicrous dances. The largest Nūl is the ‘Kalai Nūl’ and it talks about the anatomy of the body. While ‘Karna Nūl’ is on dance sequences, ‘Thala Nūl’ is about timing and rhythm. ‘Isai Nūl’ explains itself and ‘Avai Nūl’ shares details about stage design, lighting, costumes, make up and other aspects connected with the stage. ‘Kaṇ Nūl’ considers dance to be like Yoga and guides the dancer with regard to maintenance of her body and mind. These texts were meant to take the performance to the crescendo.

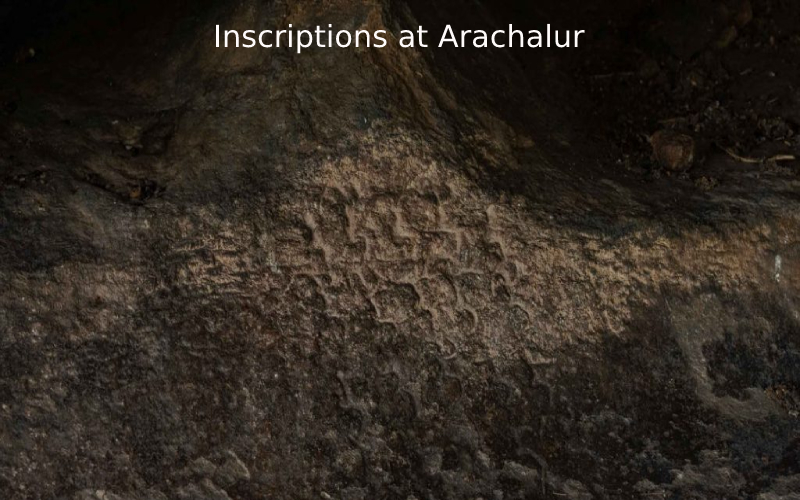

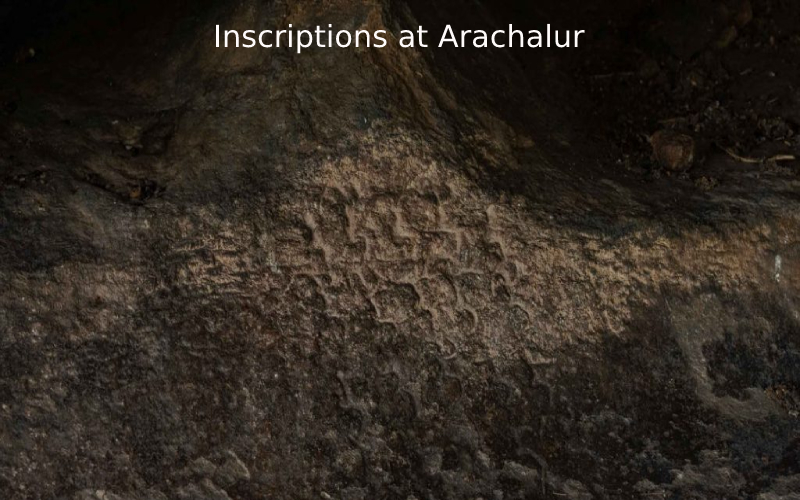

The Arachalūr descriptions on dance in Brahmi script belongs to circa 250 AD. Syllables like ‘Tha’, ‘Thai,’ and ‘Thi’ are found in these inscriptions and are still in use today. The Sittānavāsal Jain temple and several others belonging to the successive periods have depicted dancers. It was the during the Chola times that the dance culture became extremely popular. There were more than 3000 dancing girls connected with the reign of the great emperor, Raja Raja Chola (985 – 1014 AD). Inscriptions tell us that there were 400 eminent dancers attached to the Bṛhadīśvara temple and they were assorted into groups in order to perform for the commoners (Nakkan Eḍutta Padaṃ), for the nobility (Nakkan Cholakula Sundari), and for the royalty (Nakkan Rājakesari).

Several inscriptions records the land grant given to Devadāsīs and they were to perform in the temples. The 400 of them in the big temple had to perform ‘Tirumūlar Nāyanār Kūtthu’, ‘Pampuliyūr Nāḍagaṁ’, and ‘Rāja Rājeśvara Nāḍagaṁ’. There are bass reliefs connected with dance postures from ‘Nāṭyaśāstra’ with relevant verses etched at the Big Temple, Naṭarāja Temple in Chidaṁbaraṃ, and Sāraṅgapāṇi Temple at Kuṁbakoṇaṃ. The Bharatanāṭyaṃ was preserved by other rulers too. They included Pallavā-s, Pāṇdiyā-s, Nāyak-s and even the Marāṭhā-s.

Several Bhāṇi-s or styles evolved. The Pandanallur and the Vazhuvoor Bhāṇi-s continue to be quite popular. Teachers like Vazhuvoor Ramiah Pillai, K. N. Dandayudhapani Pillai are amongst the pioneers who put dance on a sound footing in modern India. In fact, Vazhuvoor Ramiah Pillai introduced the dance sequence in the first ever Tamil movie. Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai of Pandanallur was the other pioneer. His ancestors were Naṭṭuvanār-s and they descended from the Tanjāvūr Quartet who comprised of the brothers Chinnaiyyah, Ponnaiyyah, Sivanandam and Vadivel. They were the court composers in the early part of the 19th century at Tanjāvūr. Their works are part of the classical masterpieces in Bharatanāṭyaṃ. Dancers like Alarmelvalli, and Meenakshi Chittaranjan were trained under Subbaraya Pillai who followed the Pandanallur style. These names and the name of popular dance teacher, K. J. Sarasa who taught the former Chief Minister of Tami Nadu, J. Jayalalithaa. Eminent danseuse, Shobana also was trained under K. J. Sarasa. This great teacher, K. J. Sarasa was the first woman Naṭṭuvanār and was known for taking Bharatanāṭyaṃ throughout the world.

There had been and are several great dancers who have decorated the world of dance. Their names deserve to be etched in gold and placed at the feet of Lord Naṭarāja in Chidaṁbaraṃ. A Complete Dance Encyclopedia would be a best tribute to each one of them and their time. Yaamini Krishnamurthy, Mallika Sarabhai, Kanaka Sreenivasan, Sreekala Bharat, Sudharani Ragupathi, Rama Vaidyanathan, and Chandralekha were among the long list of dancers. L. Vijaya Lakshmi was one more famous actor-dancer who continued to perform overseas and is remembered for having performed during a visit of Prime Minister, Morarji Desai to Philippines. Jaya Tv promoted Bharatanāṭyaṃ in a big manner through the well-known Sunday morning program, ‘Thaka Dhimi Tha.’

The Great dancer, T. Balasaraswathi was the greatest exponent of the Devadāsī style of dancing in the 20th century. Her dance performances drew aristocratic audiences and they used to get swayed while watching her. She used to sing and dance. T. Balasaraswathi continued to teach and offer lecdoms in places like United States of America. She immortalized Bharatanāṭyaṃ and people continue to crave for the performances given by her and her likes during the yonder era.

‘Sadhir’ or ‘Nāṭyaṃ’ or ‘Bharataṃ’ is today a grand performing art. Dancers and dance teachers throughout the world continue to dedicate their time and effort in order to offer their obeisance to Lord Naṭarāja in the form of Bharatanāṭyaṃ. In Bharatanāṭyaṃ, there is individualism that prevents the art from becoming a manufactured product. This is what is keeping Bharatanāṭyaṃ alive and kicking.