Dancers and Nattuvanaars in Modi records

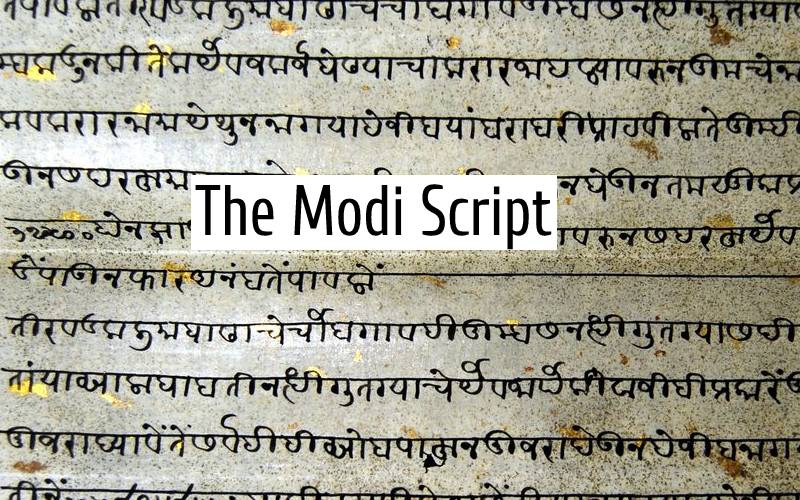

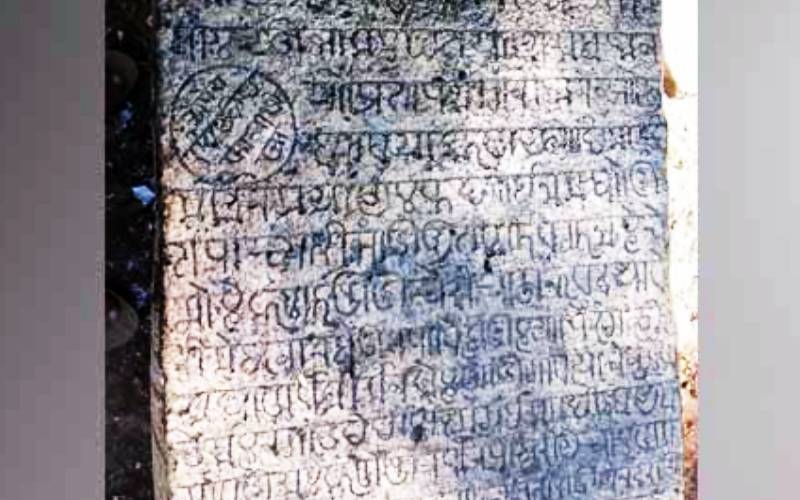

The official language of Tanjore Maraatta court is Maraatti, and a script known as Modi is used officially. The word mod in Maraatti means, to break. The standard Devanagari script was broken and modified for speedy writing, hence the name Modi in a cursive form is used for all official documents say day to day records, official correspondences for almost a century from 1676 - 1799. This can be also conveniently called as shorthand version of Maraatti.

Modi script is classified into 4 types as it underwent lot of changes during the course of time. The one used in Thanjavur is of archaic type which evolved during times of Chatrapathi Shivaji and is little difficult to read comparing to Modi that was used in Maharashtra. There are thousands of Modi manuscripts preserved in Saraswathi mahal library and Tamil university Tanjore.

These ingenious records give incredible insights into the history, administration, trade and commerce, arts and social life during Maraatta rule. It can be broadly classified into judicial, civil, financial and military administration. Miscellaneous subjects like regulations in conducting nautch parties, maharaja's travel to Benares, accounts relating to construction of drain around Tanjore, groceries bought for royal kitchen, its expense for a day and such records are also preserved until now.

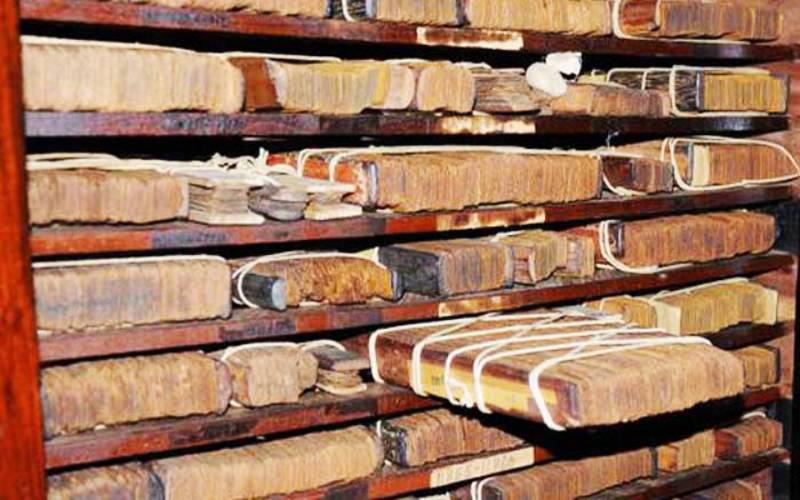

After the annexation by British, the records from 1776 to 1860 were safely stored as ‘Tanjore Raj records.’ Indian Historical Document Commission that met in 1946 in Indore decided to shift these Modi documents, called Maraatta Raj records, from Thanjavur Palace to Saraswathi Mahal Library. In 1950, the Indian Government ordered to shift them to Chennai Archives. About 960 bundles were left and remaining were sent to Delhi and Chennai.

Government provided a grant and appointed 2 Pandits to examine the available manuscripts under Major Balakrishna Gadre, a retired government servant and a scholar of high calibre. The team examined and separated them as A, B and C bundle group, where A, B were sent to Tamil Nadu Archives and C is retained in Saraswathi Mahal. It is classified and transcribed into Marathi with translations in Tamil and English. Now A and B documents were brought back to Tamil University. Oldest record available at Saraswathi Mahal dates back to 1719 A. D. The records for the period of 1676 to 1719 A. D., is much available at Tamil university.

There are 820 bundles of Modi documents in Tamil University. Every bundle has 500 to 1,000 Modi documents. From the period of Ekoji, first Maraatta king who ruled Thanjavur, to Sivaji II (1676 - 1855 A. D.), all letter communications, accounts, diary notations, and palace proceedings were done only in Modi script. Only those who know Maraatti and Modi letters can read those documents and other paper manuscripts.

Saraswathi Mahal Library had once microfilmed the Modi documents. Tamil University has taken steps to digitize, translate, and publish them into three volumes selected manuscripts of A and B Modi record bundles. The royal correspondence between French at Pondy and Tanjore Maraatta-s is in Modi script. 60 villages around Karaikkal which was under Tanjore Maraatta-s was exchanged in lieu of a loan, and thus Karaikkal became part of French territory.

Historian, K. M. Venkatramanayya, has brought a beautiful book which is based on this Modi records on administration, political and social life during Maraatta period. This book gives clear picture on various customs, practices and laws that existed during Maraatta rule. One example is, if a person resides in a home for 30 years legally, he becomes owner to that is described. Coins, land survey, judicial administration, temple rituals, growth of music, dance and drama, medicine, customs and practices at the palace are vividly described.

There is a Modi record which speaks about an appointment of an employee with salary of 3.50 rupees to maintain and preserve manuscripts at Seroboji library. The contribution of Maraatta kings to fine arts is immense. They were not only mere patrons but good composers and artists themselves. Modi records speak in detail of their contribution, patronage of each king to drama, music and dance as well as art scenario. This Modi records is a treasure trove and I present here few information regarding dance.

There is lot of info about nattuvanaar-s and dancers. Frequent dance programs were held at the palace. The do-s and don't-s of nattuvanaar-s and dancers, both who were in service under temples and the palace, are prescribed in a record dated 1846. Presenting below a few from it.

Vaira Rakidi, Besari, Attikai, Velli Metti should not be worn. Kumkum should not be adorned in a large horizontal line in forehead. Few specific blouses should not be worn, and ornamental coil should not be used. While dancing in palace, narasthuthi should be avoided, and only abhinaya for songs on God or Maharaja is allowed. Nattuvanar-s should wear shawl or tuppatta around his neck. Slippers and head gears are prohibited.

These restrictions are relaxed for a dancer named Sundari who had few other privileges too. Dancers under palace payroll was prohibited to perform outside without permission from palace and those who disobeyed were punished. Ladies acted in drama. “Mridangam vasigira Kamatchi” with these words in a document, we understand that ladies were playing mridangam. A stipend is granted to Dancers who were dedicated to temple service from palace and a monthly salary is also fixed. She is free to leave temple service, if she wants to enter into marriage alliance.

Ladies were also purchased for temple service is evident from a record it says, from Sarabendra Pattanam one dhaasi,

Ramamani, and five others were bought for Chidambareswarar temple. The salary per month was 5 panam and 2 kalam-s of paddy. This temple dancers had patrons and bore kids with them and female kids of this dancers who is not pretty and who do not possess qualities of a dancer are married off through a ritual called Pottu kattal at a very young age. A record from 1842 talks about Annam Dhaasi. She was aged 10 with her fixed salary, paddy 1 kalam per month and sadam pattai 1.5 on daily basis. The dancers bought for a temple was also transferred to another place as per requirement.

During the period of Seroboji II, there lived a dhaasi named Veeralakshmi. She along with her four daughters was employed in Chidambareswara temple at Sarabendra Pattanam for a salary of 5 panam and 2 kalam of paddy. After Serobhoji, during the period of Sivaji they were paid from the account of Sivangikottai. Then by 1840, they came under Sangeethapathak, and finally, they were kept under the account of Kutcheri. When Sivaji passed away their salary was stopped. But later it was paid along with arrears. From this we can understand that a mother along with her kids were dedicated to temple service and noteworthy is that they were not separated.

A dancer from one temple is allowed to be dedicated to another temple. A record from 1882 mentions a Kuluvai aged 12 and Kambalayam aged 10 were transferred from Kamatchiamman temple to Tanjore big temple. Dancers who did not stop when a British officer passed by the road in a vehicle were punished. Names of musicians and dancers under palace payroll, their salary and gift details, dance program and participant detail, appeals to government, cases related to them, punishments and many interesting incidents can be seen in Modi documents. The list is big so restricting to this much alone. This is a mirror to the period of Tanjore Maraattas and therefore careful preservation and translation of all the records would be of immense benefit. Unfortunately, the people who can read this script is very less now which makes the task tedious.

S. Gnanaprakash is history, religion, dance, and music enthusiast. He serves in the IT sector. He is keen to establish a cultural centre and a temple in the near future. His vast collection of books, videos, audios along with fine copies of art are one of its kind in Western Tamil Nadu.

S. Gnanaprakash is history, religion, dance, and music enthusiast. He serves in the IT sector. He is keen to establish a cultural centre and a temple in the near future. His vast collection of books, videos, audios along with fine copies of art are one of its kind in Western Tamil Nadu.

S. Gnanaprakash is history, religion, dance, and music enthusiast. He serves in the IT sector. He is keen to establish a cultural centre and a temple in the near future. His vast collection of books, videos, audios along with fine copies of art are one of its kind in Western Tamil Nadu.

S. Gnanaprakash is history, religion, dance, and music enthusiast. He serves in the IT sector. He is keen to establish a cultural centre and a temple in the near future. His vast collection of books, videos, audios along with fine copies of art are one of its kind in Western Tamil Nadu.