During the colonial period, both the Khasi and the Jaintia communities of Meghalaya were referred to as Khasis. After the first Anglo-Burmese war (1824-1826), the British Government decided to occupy the Brahmaputra with the ostensible purpose of connecting the two valleys of the Brahmaputra and the Surma by an all-weather road through the Hima Nongkhlaw territory of the Khasis. Nongkhlaw was then an illustrious Khasi kingdom in the mid-western Khasi hills of Meghalaya. The Surma Valley formed the boundary between the British possessions and the Jaintia kingdom.

The construction of this road to link the two important British headquarters – Kamrup (currently Guwahati) with Sylhet (present-day Bangladesh) – was of strategic importance for the British, to improve the road communication between the Brahmaputra and the Surma Valleys. It would also have ensured the speedy and safe movement of their troops. The British were forcefully penetrating into the hills, occupying their lands and controlling its people. Turmoil first began in the Jaintia Hills (the erstwhile Jaintia kingdom was formerly known as Jaintiapur) in the year 1827 which soon spread to the neighbouring Garo Hills.

The Jaintias, at that time, were largely concentrated in the easternmost part of the Khasi and the Jaintia hills. As per historical records, the Jaintia Kingdom was established in 1500 A.D. The Jaintias, like the Khasis and the Garos, still reckon their descent through the female line. They believe that the world is ruled by the supreme Devi called Ka Blai Synshar (Ka meaning ‘she’). Their indigenous religion is known as Ka Niam.

A popular belief prevalent in the region is that the origins of the word ‘Jaintia’ may be traced to Jayanti Devi (believed to be Bhadrakali), worshipped by the Jaintia royal family during the 16th century after consolidating its sway over the plains tracts in the south. The non-Christian Jaintias (numbering around 100 families) are still the caretakers of the famous Durga Nartiang Shaktipeeth situated at Jowai, Meghalaya. Every year, they also visit the Kamakhya Shaktipeeth at Guwahati during the annual Ambubachi (menstrual cycle) celebrations of the Devi.

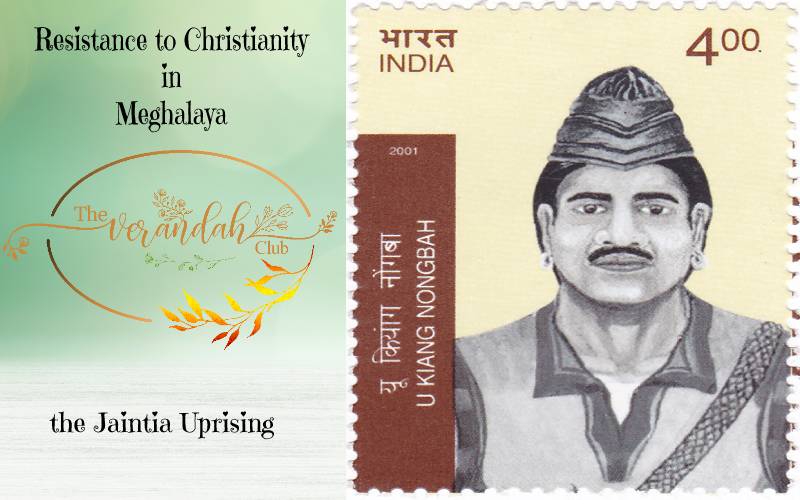

U Kiang Nangbah – The Hero

U Kiang Nangbah was the key person behind the Jaintia uprising in Meghalaya. Not much historical material is available to guide us in revisiting the life story of this great man, his childhood and education, and the resistance movement that he started against the British. The local oral tradition of the Jaintias tells us that Kiang Nangbah was born in a poor farming family to Ka Rimai Nangbah in a locality called Tpep-Pale in Jowai, situated in the West Jaintia Hills District of Meghalaya. Thus, Kiang Nangbah had no royal lineage whatsoever.

Nangbah belonged to the Syngkon sub-clan of the Soo kpoh khad-ar wyrnai clan (kur), which was started by the four progenitors of ka Bon, ka Tein, ka Wet, and ka Doh, the founding female deities and the first settlers of Jowai. Hence, it has been proved beyond doubt that U Kiang Nangbah was from Jowai and belonged to the sookpoh clan, because his last rites were performed by someone from the same clan. Nangbah was a curious child who listened with rapt attention to the explanations provided by his elders to his queries. Being the only child in the family, Kiang Nangbah led a solitary life.

He did not receive any formal education but was taught by his mother at home about the rights and duties of a responsible citizen. “They are foreigners and they want us to be their slaves” – said his mother one day to Kiang Nangbah. As a teenager, Nangbah was deeply distraught by the atrocities committed by the British on his people. He was quick to realise that a disciplined fighting force was the most important need of the hour which would help the natives challenge the military might of the British.

The Coming of the British & the Christian Missions

A series of measures were introduced in the Jaintia Kingdom under the ‘Forward Policy’ of the Government. Raja Rajendra Singh of Jaintiapur, the then king of the Jaintia Kingdom, was deprived of his dominion through deceit. The British had asked Rajendra Singh to sign a new treaty which clearly stated that he should pay an annual tribute of 10,000 rupees. But, the terms of the new agreement were stoically declined by him.

It was in the year 1853 that A.J.M. Mills who was the judge of the Sadar Diwani Adalat, on deputation to the Khasi and Jaintia hills, advocated the imposition of a house tax. He further suggested that a thana (police station) was to be set up so that strict vigilance on the “unruly conduct” of some people in the area could be maintained. The Jaintias were never accustomed to paying any money tax in the past, but annually used to send one male goat and a few seers of parched rice from each village as homage to their king, who derived a greater portion of his income from the plains.

When Kiang Nangbah came to know about the house tax, he declared that this was an extremely absurd idea. Three British police stations were destroyed by an angry mob who was agitated at the ongoing state of affairs. Nangbah could foresee in advance a series of changes which would eventually spell disaster to the Jaintias’ social systems, laws and customs, and institutions. A decree was passed by the government which declared that taxes should be paid by everyone, and anyone who failed to do so would be dealt with severely.

When the British officials attempted to collect tax from one Lakhi Pyrding, a poor Jaintia farming woman, she refused to pay the tax. Humiliated by this refusal, they ransacked the house of the woman and looted all her valuables too. Upon hearing about the incident, Nangbah was furious. He arrived at the spot and fought against the armed officials almost single-handedly. In 1861, the British administration considered the imposition of income tax on the local population which would be increased further every year. This was completely insensitive.

Another apprehension which was doing the rounds was that taxes could be levied on betel leaves and betel-nut as well, the two essential items used in Jaintia religious ceremonies. Such arbitrary policies of the colonial administration during the 1850s and the 1860s angered the Jaintias, eventually compelling them to openly rebel against the colonialists. It was at this juncture that Kiang Nangbah signalled the beginning of a revolt against the brutal authoritarianism of the colonial state.

Led by visionaries like Nangbah, U Bang Doloi, and U Myllon Doloi, the Jaintias declared complete withdrawal of the British from the Jaintia hills. They were assisted by the Khasis and the Garos alike by blocking lines of communication, laying ambushes and creating havocs on the Sohra-Jaintiapur and Jowai roads. Nangbah openly declared that his people were not entitled to pay any form of taxes imposed by a foreign ruling power. He refused to recognise British control over the Jaintia Kingdom, because of the way the latter was deceitfully acceded to the Empire and the king unceremoniously removed from his throne by the British.

A police station and a Christian missionary school were established at Jowai in 1855 with the objective of establishing “Government authority” over the hills. Since the police outpost was set up near the cremation ground of the Dkhar clan of the Jaintias, it was looked upon as a symbol of intrusion. Previously, in the year 1842, the Bible had been preached for the first time in Jowai by Rev. Thomas Jones.

During the initial stages, the coming of the Welsh missionaries into the hills was not at all liked by the Jaintias who were the ardent followers of their indigenous religion Ka Niam. Several restrictions were placed on them by the Church, e.g. the newly converted Christians among the Jaintias were strictly debarred from attending their traditional festivals. As a penalty for those who refused to comply with the directions, the Church had the right to excommunicate them from its congregations.

Consequently, the Government took several additional measures to control them and assert its power further. E.g. an order was issued which directed the people to not burn their dead bodies near the military outpost. This was one of the major incidents that seriously enraged Nangbah and his people. The foreigners were disrupting their ways of living, and preventing them from performing their cultural and religious obligations as had been practised so far.

Music was a passion for Kiang Nangbah. Hence, the British high-handedness was explicitly visible to him when the swords, shields, and other musical instruments such as the Ksein Kynring (a special drum made from the wood of a tree worshipped by the Jaintias of Shangpung), were forcibly confiscated, desecrated and burnt by the local police led by the Naib Darogah of the Jowai police station. This particular incident of religious intolerance took place at Jalong village during the performance of the Jaintia traditional warrior dance called Ka Pastieh Kaiksoo. The celebration was abruptly interrupted by the police before a large number of people who had gathered to witness the dance performance.

It proved to be the last straw in the already strained relationship between the Jaintias and the British. Jaintia religious places were earlier destroyed by the British in order to facilitate the entry of the Protestant missionaries. Moreover, in the year 1860, a police constable shot dead an aged monkey in the nearby sacred forests of the Jaintia Kingdom. The Jaintias had always lived in a profound communion with nature since times immemorial. Their traditional religious rituals played an important role in the conservation of nature, with many villages dedicating a part of the forest as sacred groves (known as Khlaw U Blei or Khloo Blai/Khloo Langdoh in Jaintia). The Jaintias could now feel a serious crisis of identity and hence could not reconcile their fate as subjects under the British rule.

The Rebellion & Kiang Nangbah’s Role

Beginning on December 28-29, 1861 the Jaintias, led by Kiang Nangbah, fought a bitter war of attrition for almost three years (1860-63) against the British. Nangbah travelled all over the Jaintia Kingdom and even into the neighbouring Khasi states so as to seek support from the people. Very soon, he won the respect and admiration of all for his qualities of bravery and selflessness.

On January 20, 1862 the entire Jaintia hills district was up in flames. The local police station and the treasury office at Jowai were burnt down by angry villagers, destroying them completely. They also set fire to its storehouse of weaponry and arsenal. The initial spark was provided by the murder of two British soldiers who were dak-runners carrying messages from Nartiang to Myntang. These events took place only a few years after 1857.

Jowai, which was besieged by the rebels for almost three weeks, was re-occupied by the British amidst heavy mass casualties on both the sides. It was not easy for the local officials posted in the area to stem the tide. The highly skilled Nangbah and his strategic tactics to fight the British soon became the talk of the town. He evaded arrest through his secret military tactics. The British Intelligence Service too, failed to trace his movements and activities.

A popular story about Nangbah goes so that he once struck an elderly man hard when the man had scoffed at him for wearing his traditional dress, i.e. the dhoti, and playing the flute by the riverside. When summoned before the Dorbar (village court), he defended himself so well that it had to finally declare him not guilty of the charge and was instead praised for his profound sense of patriotism. The members presiding over the Dorbar were deeply moved when he stated that it was better for him to die than be deprived of his personal freedom.

It was under the able leadership of Nangbah that the Jaintias burnt down several Christian settlements in Jowai and its neighbouring areas and besieged the military outpost. They waged a guerrilla warfare with traditional weapons such as swords and shields, spikes and lances, etc. including canons and firelocks, which paralysed the British administration. The superiority of the British in arms and ammunition such as muskets, bayonets and artillery proved to be no match for the sharp ingenuity of the natives whose trained men through ambushes gave a tough fight to the British soldiers.

The cries of “chut ki weit hawa nep hawa nep/hawa biang ki cher ki soom/pi yong i u lai i kattu yow pyndem bait ha’u mynder ri/” (meaning, ‘Sharpen your swords folks/prepare your spikes and lances/let us march together to defeat the foreigners/) reverberated in the air. Nangbah was well-known for his deft organisational skills. By virtue of better organisation and combat capabilities, the attackers swiftly escaped to the nearby jungles of Myngkrem, Myntdu, and Myntwa in order to evade detention. Very soon, the attacks spread to the areas of Mynso, Changpung, Raliang, Nartiang, Borato, Mookaian, Sutnga, and other places of the Jaintia hills.

A wave of panic gripped the British forces which found it very difficult to suppress the rebellion at one instance. They used the influence of Ram Sing and Rabon Sing, the Rajas of Sohra and Khyriem respectively, and a few others to convince the rebels to give up their armed struggle. The British were so thoroughly demoralised that on March 28, 1862 the administration of the Jaintia hills was handed over to the then British Army Eastern Command.

The disturbances had such an impact upon the administration of the neighbouring districts that the Government had to finally depute Brigadier-General Showers with around 2,000 soldiers (mostly Sikh) to suppress the Jaintia warriors in April 1862. This happened around the same time when the captive Raja Rajendra breathed his last. To counter the rebels, the Government launched a full-scale military operation against Nangbah and his men.

The guerrilla tactics of warfare launched by the Jaintias were so effective that they stirred confusion among the British camps, which prolonged the war. However, Kiang Nangbah was grievously injured in one of the bloodiest battles. While the revolt was going on, Nangbah fell severely ill and retreated to Umkara. Historically, the cave Kut Sutiang located in the midst of a dense forest in the present-day Khasi hills of Meghalaya, is believed to have been Kiang Nangbah’s last resort in his fight against the British.

Taking this as an opportune moment, U Long Sutnga and U Tyngker, who were key members of Nangbah’s team, secretly informed about the place and condition of Kiang Nangbah to the British. In the early hours of December 27, 1862 Nangbah was arrested with the help of two other informers, from a village called Mynser (now in Karbi Anglong district of Assam), while he was still recuperating from his ill-health. It was reported that the British had also seized three guns from him after his arrest.

When Nangbah realised that his camp was being surrounded by British soldiers, he immediately fired at U Long Sutnga, the betrayer who took him to the hideout at first and then helped reveal his identity to the enemy. But, the gun got stuck somewhere and failed to fire. U Long Sutnga was saved. This implies that Kiang Nangbah perhaps used guns more than any other weapon in his fight against the British. When asked why the people revolted, he stated that it was due to the uninvited interference of the government with their ways of living and belief systems.

Nangbah was chained and paraded to Jowai on December 30, 1862. After a mock trial, he was found guilty of provoking violence and disorder. He was later hanged in full public view in the evening of that fateful day at the local marketplace of Iawmusiang in Galway town of Jowai, Meghalaya. Several other Jaintia warriors died fighting or in custody. He was executed within just a few hours on the day of his conviction itself. Nangbah told his weeping countrymen to watch him with courage, faith and hope while he was being swung on the rope.

A glorious chapter in the struggle for the freedom of the Jaintias of Meghalaya thus came to a close with Nangbah’s death. The condemnation of Nangbah to death and his public hanging were aimed to strike a reign of terror among the common Jaintia men and women. The revolt of the Jaintias was finally suppressed by the year 1863, through both punitive and diplomatic measures. Nangbah’s spirit of patriotism and undying love for his motherland still remains alive in the hearts and minds of the people of Meghalaya through various media such as poems, art, folk songs, ballads, etc.

The state Government of Meghalaya has declared December 30 as a state holiday in honour of this brave son. Every year, the Government confers a State Award called the Kiang Nangbah Award upon the most outstanding sportsperson of the state. Various cultural programmes are organised across different places of the state on this day which is popularly commemorated as U Kiang Nangbah Day. A government degree college was also opened at Jowai on September 15, 1967 in the loving memory of Kiang Nangbah.

A postage stamp was issued by the Government of India in July, 2001 to commemorate this lesser-known/unsung freedom fighter from Poorvottar Bharat. On December 30, 2014 the Khasi Students’ Union (KSU), Meghalaya, in association with the North-East Students’ Organisation (NESO) and the Syiem-Jaintia Women’s Wing, had unveiled a life-size statue of Nangbah in his war attire at Barik near the Civil Hospital junction (along the Shillong-Jowai road), on the occasion of his 152nd death anniversary. Today perhaps, the identity of the non-Christian Jaintias would have been lost, had it not been for the efforts and sacrifices of this great leader.

References:

Amarendra Kr. Thakur. (2014). Resistance to British Power in the Hills of North-East India: Some Issues. Dialogue, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 117-128.

Dr. Harish Shetty. U Kiang Nangbah: A Forgotten Hero of North-East India. https://mindmoodsandmagic.blogspot.com/2012/08/u-kiang-nangbah-forgotten-hero-of-north.html?view=sidebar&m=1

Shobhan N. Lamare. (2017). Resistance Movements In North-East India: The Jaintias of Meghalaya 1860-1863. Regency Publications, New Delhi.

Shobhan N. Lamare. (2005). The Jaintias: Studies in Society & Change. Regency Publications, New Delhi.

Acknowledgement: A sincere note of thanks to all my team members who have helped me gather materials on these subjects, especially Delina Khandup Ma’m, for enlightening me about Pastieh Kaiksoo and the Jaintias.

(Th e author is a researcher on the culture and history of Poorvottar Bharat. She is also a regular columnist for various newspapers and online portals).

e author is a researcher on the culture and history of Poorvottar Bharat. She is also a regular columnist for various newspapers and online portals).

NEXT ARTICLE

At the southernmost tip of this mesmerising ensemble lies the majestic Great Nicobar Island, boasting an impressive landmass of about 910 square kilom...

Bharath has always been a land traversed by spiritual masters/ Guru since time immemorial. These spiritual masters have always upheld the core princip...

South India contains its fair share of unique pilgrimage centres. These divine places of worship have a prominent Sthala Purana, devoted followers, di...