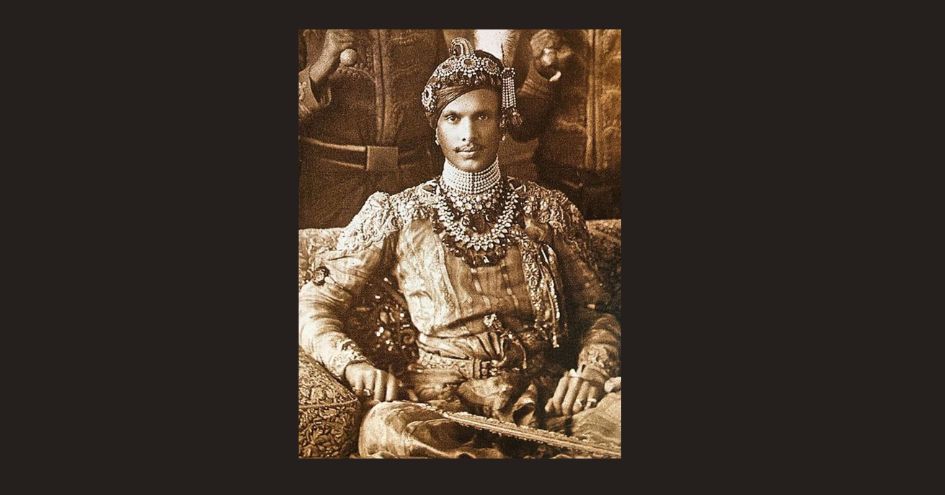

The Accession of Jai Singh Prabhakar (1892)

In the princely state of Alwar, located in present-day Rajasthan, 1892 marked a turning point in its royal history. The throne had fallen vacant upon the death of Maharaja Mangal Singh, a ruler whose reign had been turbulent and controversial due to his friction with the British colonial authorities.

Maharaja Mangal Singh was dismissed by the British in 1891 due to what they considered maladministration and his inability to govern effectively. He died shortly thereafter under circumstances that remain murky. His sudden death left a vacuum at the top of the princely hierarchy and an urgent need for a new ruler who would both stabilise the state and be acceptable to the British Raj.

Into this power vacuum stepped Jai Singh, then a 10-year-old boy from the Narayani branch of the Kachwaha Rajput clan, a collateral line of the Alwar royal family. He was not a direct son of the previous Maharaja, but was selected and adopted as the heir to the throne by the British Political Department, which had considerable say in such successions under the doctrine of paramountcy.

This decision was not without its political calculus. The British viewed the young Jai Singh as malleable, someone they could shape into a loyal prince who would rule under their guidance and preserve British interests in the strategically important Alwar state.

Thus, in 1892, Jai Singh was formally installed as Maharaja of Alwar, though as a minor, he could not yet govern independently. A Council of Regency, made up of senior administrators and under the supervision of the British Political Agent, took charge of state affairs during his minority.

The Regency Years (1892–1903)

The regency period was meant to train the young Jai Singh in statecraft, governance, and diplomacy. He was given a thorough education, both in traditional Rajput martial values and in Western political and administrative practices. His tutors included British officers and Indian scholars, ensuring he would be both grounded in Indian tradition and conversant with colonial expectations. This period deeply influenced Jai Singh. While he emerged as a capable and modern-minded ruler, it also planted in him a desire to assert himself, especially as he matured and came to resent the constant interference of the British in princely affairs.

In 1903, upon reaching the age of 21, Maharaja Jai Singh assumed full ruling powers. What followed was a dramatic and eventful reign, marked by attempts to modernise Alwar and maintain dignity in the face of colonial pressures.

Maharaja Sir Jai Singh Prabhakar of Alwar grew to be a visionary and reform-minded princely ruler of his time. His reign (1903–1933, after assuming full powers) saw several progressive initiatives that reflected his ambition to modernise Alwar — not just in appearance but in its infrastructure, administration, education, and culture.

1. Infrastructure & Public Works:

Roads and Railways: Jai Singh undertook massive efforts to improve connectivity within Alwar. Roads were extended, upgraded, and maintained to enhance trade and movement. He also supported railway expansion, linking Alwar more effectively with nearby states and British India.

Water Supply Projects: He implemented water management systems including reservoirs and public fountains, and improved irrigation for agriculture. Electricity & Telecommunication: Alwar became one of the first princely states to introduce electricity in urban areas. Telegraph and postal services were modernised, enhancing communication.

2. Administrative Reforms:

He introduced modern bureaucratic systems, inspired by both Indian and Western governance.

Revenue and Land Reforms: Jai Singh rationalised land revenue collection and tried to reduce the arbitrary powers of jagirdars (landed elites). He also introduced land surveys and cadastral mapping for fairer taxation. He set up civil and criminal courts, based on codified laws, to bring consistency and justice to the legal system.

3. Education and Learning:

Jai Singh was a passionate advocate of education. He established modern schools, including those for girls. He started technical institutions to impart vocational training and started libraries and scholarships to promote higher studies. He promoted Hindi and Sanskrit learning and supported the printing of classical Indian texts.

He was also a patron of scholars, poets, and historians. Jai Singh was Western-educated and fluent in English — yet he never became an imitator of British norms. He wore traditional Rajput attire at public functions, maintained Indian courtly etiquette, and resisted cultural subjugation. He built institutions that blended Indian values with modern systems, not Western imitations.

4. Health and Sanitation:

Modern hospitals and dispensaries were opened. He introduced vaccination drives, especially against smallpox, which was still prevalent in many parts of India at the time. Urban planning in Alwar saw an emphasis on clean drinking water, drainage systems, and public hygiene.

5. Patron of Arts and Heritage:

Jai Singh expanded the Alwar museum, making it a repository of rare coins, manuscripts, and art objects. He encouraged architecture in Indo-Saracenic and Rajput revivalist styles — some of which still stand today in Alwar city. He collected works of art from across India and Europe.

6. Promotion of National Consciousness

Though officially loyal to the British crown, Jai Singh discreetly supported Hindu reform movements like the Arya Samaj, which focused on education, social reform, and revival of Indian values. His support for the Arya Samaj, a reformist Hindu movement often clashed with colonial authorities due to its nationalist undertones. By endorsing this movement, he backed social reform rooted in Indian tradition — not British ideals.

He emphasised Hindi over Urdu or English in administration — a cultural and political statement. He also helped fund Indian publications and nationalist voices, indirectly fueling an emerging political consciousness. The British expected princely rulers to be decorative figureheads — Jai Singh, on the contrary, wanted to be an active, reformist, and dignified monarch. He funded Indian intellectuals and journalists who criticised colonial rule, albeit discreetly. His vision was of a self-respecting Indian state that stood tall within the Empire, not crawling under its weight.

Challenges to Modernisation

While his reforms were bold, Jai Singh faced constant scrutiny from the British, who saw any sign of political or cultural assertion as disloyalty. At imperial durbars and ceremonial occasions, Jai Singh maintained strict royal protocol, often equal to or above what the British allowed. He ensured that Alwar's representation reflected sovereignty and pride, not colonial subordination.

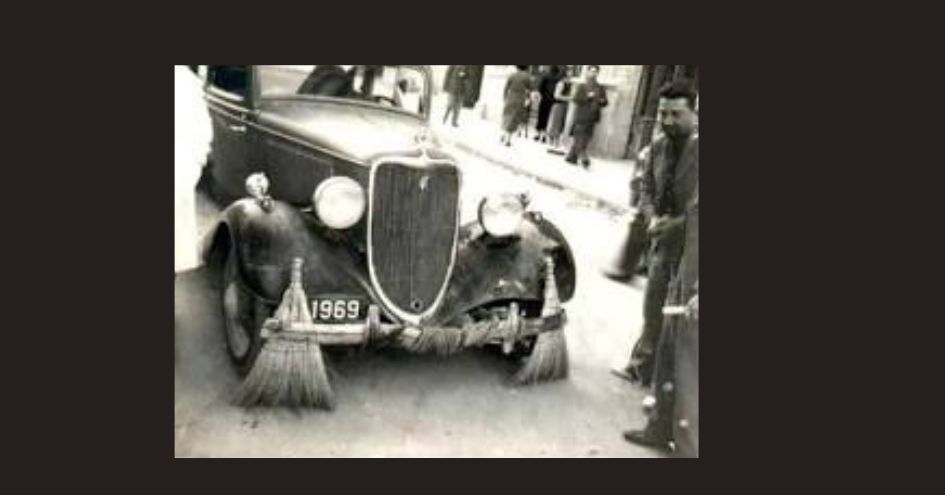

Once, in 1920, Maharaja Jai Singh visited London and walked into a Rolls-Royce showroom to purchase a car. The British salesmen, seeing an Indian in ordinary clothes, insulted him and refused to sell him a car, mocking him as someone who couldn’t afford such a luxury. Angered by the insult, Jai Singh returned to the showroom later in full royal regalia, bought multiple Rolls-Royces, had them shipped to Alwar, and then ordered them to be used for garbage collection in the city—sweeping streets and collecting trash. The prestige of Rolls-Royce took a hit when the news spread, and the company allegedly apologised profusely and begged the Maharaja to stop the humiliation campaign.

When the British attempted to reduce Alwar’s gun salute rank (a measure of prestige), he protested firmly, considering it a direct affront to his state's honour. His growing independence irked the British, who viewed him as a "difficult" ruler. His attempts to balance progressive governance with regional pride eventually led to tensions that culminated in his forced abdication in 1933.

No Trial. No Appeal. Only Exile.

There was no public trial. No chance to defend himself. The British pressured the Maharaja to abdicate, quietly, without protest — to “preserve the honour of the throne.”

And Jai Singh, proud as ever, refused to beg or barter. He signed the abdication papers in silence, his pen firm, his voice steady, his heart breaking. In 1933, he was stripped of all powers and exiled from his kingdom. A man who had ruled with vision and modernity was reduced to a silent observer of history.

The Aftermath: A Ruler Without a Kingdom

After his abdication, Jai Singh lived in quiet dignity, far from the palace he built, the roads he laid, the institutions he founded. He was never charged, never convicted — just erased. He never returned to public life and never wrote a memoir. His silence was louder than a protest.

What remained was the deep sadness of a fallen prince who had tried to walk the fine line between loyalty and dignity — and paid the price for daring to be proud in an empire that demanded submission.

A Symbol of Betrayed Idealism

Today, the story of Maharaja Jai Singh’s abdication is more than just a personal tragedy — it is a symbol of how the British crushed indigenous excellence when it didn't conform to their control. His fall was not for failure — it was for refusing to fail in the way the British wanted. He did not fight with arms, but with integrity, intelligence, and ideals — and it was these that made him dangerous to an empire built on fear and flattery.

As One Courtier Later Said:

“He ruled like a lion among sheep. And lions, the Empire could not allow them to roam free.”

The tragedy of Maharaja Jai Singh Prabhakar’s forced abdication in 1933 did not end with his humiliation. What followed was a slow but deliberate unravelling of Alwar's dignity, autonomy, and vision, orchestrated by the British Raj. It was a textbook example of colonial vindictiveness, camouflaged as “administrative correction.”

After the Fall: What the British Did to Alwar

1. Puppet Governance Installed

After forcing Jai Singh out, the British placed Alwar under “direct supervision”, invoking Article 45 of the Indian States' governance protocol. This effectively meant all real power was transferred to the British Resident. A Regency Council was formed, filled with compliant nobles and bureaucrats who followed British orders without question. The next ruler, a minor, was kept under British influence — ensuring that no independent thought could rise again. Alwar went from a reforming, self-governing state to a client territory under colonial control.

2. Systematic Dismantling of Jai Singh’s Reforms

Jai Singh had promoted education in Indian languages, supported Hindu reform movements, and emphasised local employment. The British rolled back or sidelined many of these programs. Sanskrit and Hindi institutions lost royal patronage. Arya Samaj supporters were harassed or marginalised. British-educated bureaucrats — often outsiders — were imposed, displacing local talent.

What was once a model of cultural self-confidence was re-engineered into a servile princely bureaucracy.

3. Character Assassination of Jai Singh

Even after his abdication, the British were not done. Colonial records and press propaganda portrayed Jai Singh as decadent, unstable, and even morally unfit.

They planted stories implying he had lost touch with reality or run his court like a personal fiefdom. These narratives were crafted not to inform but to warn other princely states: “This is what happens if you challenge British authority.” Jai Singh was erased from history books as a visionary — remembered instead as a cautionary tale. A lion recast as a fallen fool.

4. Humiliation of the Alwar Court

Ceremonial honours — like gun salutes, protocol rank, and Durbar precedence — were downgraded. British officers now dictated court etiquette, placing themselves above traditional nobles. Festivals, royal hunts, and religious occasions were subject to British approval — a cultural castration of Alwar’s heritage. The once-proud Rajput court of Alwar became a shadow of itself, stripped of the royal self-respect that Jai Singh had upheld.

5. Fiscal Intrusion and Resource Control

Alwar’s finances were now under British auditors, who froze or redirected funds meant for local development. Military units loyal to Jai Singh were disbanded or merged with British-supervised forces. Land revenues — a major source of state income — were now channelled into projects that served colonial interests, not public welfare. The kingdom’s economic spine was weakened, leaving it dependent and voiceless.

"They didn’t just remove a king, they removed a memory, a movement, and a moment of Rajput self-respect."

The British never wanted to govern India in partnership — they wanted obedience. Maharaja Jai Singh, with all his flaws, was a proud Indian ruler who had envisioned a self-reliant state within the Empire. That vision had to be destroyed.

So the British: Discredited the man, destroyed the legacy, and defanged the state— all without firing a single shot.

Wing Commander BS Sudarshan is a former Indian Air Force pilot with over 12,000 flying hours. He participated in Operation Pawan and Operation Cactus before he transitioned to civil aviation. A passionate writer, he has authored six books, including "Hasiru Hampe", appreciated by S L Bhyrappa, and the latest "Evergreen Hampi". He is a regular contributor to the Verandah Club.

Wing Commander BS Sudarshan is a former Indian Air Force pilot with over 12,000 flying hours. He participated in Operation Pawan and Operation Cactus before he transitioned to civil aviation. A passionate writer, he has authored six books, including "Hasiru Hampe", appreciated by S L Bhyrappa, and the latest "Evergreen Hampi". He is a regular contributor to the Verandah Club.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

The Venkateshwara Swami Temple in Tirupati is among the holiest places in the world for Hindus. Millions of people throng the temple every year to get...

It is a sad reality that our Itihasa and Puranas have been subject to severe distortion over the years. This is not surprising considering how even th...

The holy land of Bharat follows Sanatana Dharma. The word Sanatana Dharma is a Sanskrit word meaning, “Eternal law”. It is the indestructible ultimate...