Ever heard about the Panchatantra? Of course we have! It is a story of Vishnu Sharma, an Indian scholar educating the three princes who are complete dullards using animal fables to teach about life science (dharma) and political science (niti) to them. This story has been widely translated into a wide variety of languages from Persian to Czech.

There is nothing new about using fables to teach something valuable to the listener or the reader. In fact, it is a tactic utilized in the Upanishads and Itihasa of Bharatvarsha to teach valuable life lessons and to explain highly complex metaphysical concepts of Sanatana Dharma in simpler terms. In fact, these tales are significant even today as they help us grapple with the reality of the times we live in, be it our domestic challenge and global threats. Be it our internal turmoils or external difficulties. Because in every challenge and threat, there is a strength to be discovered and an opportunity to be exploited.

It is for this reason that the collection of stories like the Panchatantra, Aesop’s fables and 1001 Arabian Nights are so catchy. They are able to capture the public’s imagination with simple stories while explaining valuable lessons and concepts of life that lengthy lectures would be unable to. They serve as life manuals which highlight how one has to live within life’s framework and make the most out of it while living to adhere to one’s dharma and follow the principles of niti.

It is along these lines of thought that another work also was authored by the great Sanskrit writer and poet, Dandin in the 7th Century C.E. in the Pallava Court of Kanchipuram. Called the Dasakumaracharita or the “Tales of the Ten princes,” it tells the stories of ten separated princes and minister’s sons of a fallen kingdom who use their cunning and wits to win several other kingdoms for themselves. These kingdoms which are annexed using tactics and schemes instead of classic warfare either to displace inattentive and unworthy kings or to fight off usurpers who had unjustly seized those respective kingdoms from their rightful claimants. This beautifully written prose ballad has the tenets of Dharma and Niti couched in colourful and comic stories with thrilling elements of adventure and romance. It loosely provides lessons of ancient Indian strategies using the exploits of the princes to convey the messages. Further, it shows how interconnected we were even in those times, showing places like Kanchipuram (Tamizh Nadu), Ujjain (Madhya Pradesh), Champa (Bihar), Kashi (Uttar Pradesh), Kalinga (Odisha), Pataliputra (Bihar), Mathura (Uttar Pradesh) travelled through routes in the Vindhya mountains, Vidarbha region of present day Maharashtra and the Lata region in Gujarat, among others.

The Dasakumaracharita was written during the time of Dandin’s extended tenure at the Pallava Court as a literary luminary icon possibly during the reigns of King Parameshwaravarman I Pallava and King Narasimhavarman II Pallava. It was during Dandin’s tenure at their Kanchi Court that he witnessed some of the tumultuous times that the dynasty ever faced. Dandin at Kanchipuram would witness the Chalukyas, the arch-rivals of the Pallavas, restore their imperial power and position under Vikramaditya I Chalukya in response to the temporary conquest and sacking of the Chalukya capital of Vatapi at the hands of the resurgent Pallavas under the reign of Narasimhavarman I Pallava.

The Pallavas had earlier attacked and sacked Vatapi to avenge the prior loss of the Pallava king, Mahendravarman I by the Chalukya emperor, Pulakeshin II. Vikramaditya, burning with fury, marched upon Kanchipuram with his forces and put the Pallava king of that time, Parameshwaravarman I, to flight, displacing the royal court of Kanchipuram and therefore Dandin too.

Dandin is said to have roamed rural Tamizhakam at that time for years while Parameshwaravarman retreated to the Andhra regions which were the ancestral home of the Pallavas. However, Parameshwaravarman recovered his strength eventually and his armies fell upon Vikramaditya Chalukya’s forces, when they were relaxed, to oust them from Kanchipuram and retake his capital city.

The Pallava Court was soon established again and Dandin made his happy return to Kanchipuram. The Dasakumaracharita may have been written keeping these situations in mind for there are kings in those stories who are displaced by clever princes because they are either careless, or given too much pleasure. When Pulakeshin breached Pallava frontiers, Mahendravarman had spent much of his time patronising the arts and composing illuminating works himself, while Pulakeshin had rapidly grown in power and marched upon him. While Mahendravarman had kept his seat of power, Kanchipuram, he had to cede his northern territories of Tondaimandalam to the Chalukyan invaders which was seen as shameful for Narasimhavarman I, his successor.

Therefore, when Narasimhavarman ascended the throne, he rapidly militarised his army and marched upon Pulakeshin when he was distracted with a rebellion in the north of his empire, effectively slaughtering Pulakeshin on the battlefield and taking the Chalukyan capital of Vatapi. This led to a horrifying loop of vengeance where Vikramaditya I Chalukya, marched upon Parameshwaravarman I Pallava, a later successor of Narasimhavarman I to conquer Kanchi. However, much to Parameshwara’s merit, he did successfully retake his capital from the jaws of the Chalukyas and sent them packing back to their empire.

In this loop of conquered and freed kingdoms, an amazing link has been found between Dandin’s epic work and the fall of the Vakataka kingdom of the Deccan in the early 6th century C.E. For those who do not know the Vakatakas– they had ties to the Imperial Guptas, who presided over one of the “golden–ages” of Indian civilisation.

There are theories which state that Dandin’s great grandfather was a courtier of the Vatsagulma branch of the Vakatakas named Damodara and that when the Vakataka kingdom collapsed due to the indulgences and profligacy of the last Vakataka ruler, Damodara’s life was uprooted and he was forced to flee south. He eventually served under the Western Ganga king named Durvinita of Karnataka and the Pallava king, Simhavishnu in the 6th Century C.E.. Eventually his descendant, Dandin would possibly serve under Narasimhavarman II Pallava where he would pen this great ballad of his.

Peculiarly, we see these themes in history quite frequently where despite powerful rulers taking their empires to great heights, their successors immediately cause the disintegration of these empires due to indulgence and weakness which causes the loss of their thrones and the establishment of a new dynasty. For instance, the Vatsagulma Vakataka king, Hasrishena was the mightiest king of his branch and a great patron of the arts. He was said to have had influence all over the Deccan and central Bharatvarsha. He patronised some of the excavations and decorations at the Ajanta Cave Complex, giving the world breathtaking masterpieces captured in rock and paint. However, when Harishena’s reign ended, his empire steadily declined at the hands of his successors who were wasteful, indulgent and reckless. The empire splintered and the Kalachuris of Mahishmati (yes, Mahishmati is real!) and Chalukyas of Vatapi blossomed upon their ruins. In fact, Dandin’s anecdotes, though literary, hold a mirror, likening numerous literary characters to actual historical figures of the Vakataka Court and highlight the chaos in the Deccan after the Vakataka fall, with rival dynasties vying for territory and seizing chunks as they see fit.

The Chalukyas are another example, where Vikramaditya II Chalukya, the mightiest of the Chalukya monarchs (we have read about him in one of my earlier articles in Verandah Club) took his empire to its zenith, harassing and humiliating the Pallavas of Kanchipuram on numerous occasions. But after his demise, his son Kirivarman II Chalukya quickly lost ground due to weakness and this led to the establishment of the mighty Rashtrakutras of Manyakheta. So this also tells us that be it the era we live in, just because a scion hails from an eminent family, it does not mean he or she is going to achieve or do great things. Sometimes, he or she may just turn everything their ancestors built to dust!

The Pallavas, on the other hand, would survive multiple nearly fatal blows to their kingdom, springing back to life due to the sheer tenacity of its successors who resorted to all the four ancient Indian political strategies for diplomacy, governance, and conflict resolution from the Arthashastra, representing Conciliation (Sama), Gifts/Incentives (Dana), Dissension/Division (Bheda), and Force/Punishment (Danda) to survive and hold onto their kingdom.

For instance, we have Narasimhavarman I, a successor with a broken kingdom, transforming it into a Deccan superpower, destroying his arch-rivals and establishing the port city of Mamallapuram. His later successor, Narrasimhavarman II chose not to grow west where the Chalukyas had also cultivated their power base. Instead, he used Mamallapuram as a springboard and sent delegations with incentives and gifts to further his kingdom’s trade and cultural influence in the far southeast and China, across the Bay of Bengal and Indian Ocean! Further, into the future, Nandivarman II, a later Pallava would cultivate maternal alliances with the Rashtrakutas under Dantidurga, who were the succeeding dynasty to the Chalukyas, thereby securing his dynasty’s future for over a century.

Dandin’s Dasakumaracharita features deceptions, clever disguises, strategic killings, alliance-making, and reconciliations which are tactics that loosely align with the four political strategies from the Arthashastra. Like the Panchatantra, it features stories which are scandalous and graphic to read, showing a number of elements like deception, corruption in society and satire. However, the work is steeped in gritty realism, showing the truth of those times and much of what is prevalent in our times too. The princes use the means available to triumph over their rivals while protecting those whom they love. While the tenets of Dharma highlighted in these stories cannot be compromised upon, the strength to establish these tenets need not come from that of the arms, but can originate from the mind too.

In history, much like the Ajanta Caves, with its unfinished sections, show the transient nature of life and ambition, empires rose and fell due to strengths and weaknesses, with no universal reasons behind that rise and fall. But what we do know is that the methods that they used to rise to power and maintain that power was what was available to them at the time, even if considered underhanded in our times.

While we cannot judge who had Dharma on their side in these dynasties, we can accept that our ancestors did not wait for when the “push came to shove” moment to protect their way of life. What they thought was right according to their svadharma and rajdharma, they did that.

Indian history is not a colourless record of kings mindlessly squabbling among themselves for power and petty politics. There were times when kingdoms were built and saved using cunning and stratagem, embedding Indian history and literature with these rare gems of realpolitik in anecdotal formats.

In conclusion, we can clearly see how literature mirrored Indian society of its times, serving as a gateway to periods when our ancestors, despite living in different eras, experienced similar lives to ours by being driven by similar motives and goals as ours. Indian literature is a treasure trove of dharmic gems which can teach profound truths using well-written witty tales. Indian literature and Itihasa is filled with epics describing epochs celebrating the glorious civilisation of Bharat while guiding us to keep an eye on the future from the present.

Seeing Dharma from the narrow lens of ethics is foolish for the framework of this system is not merely moralistic but steeped in realism while being tempered by idealistic goals. It is these realistic means that we need to embrace to reestablish our timeless values. It is not simply that the ends justify the means that we take, but that we take realistic steps reflecting the times we live in to establish values that are timeless and eternal parts of Sanatana Dharma.

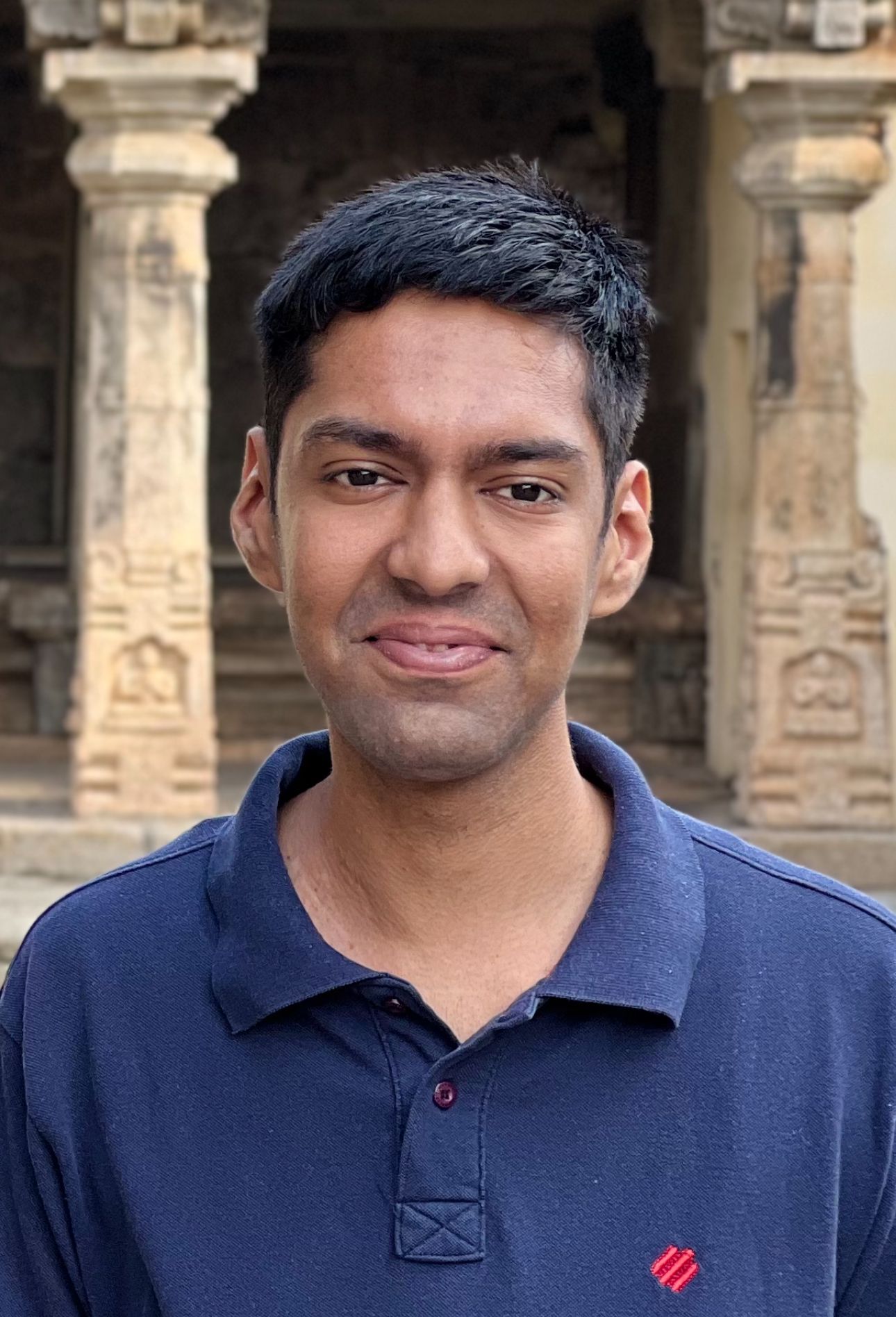

Vignesh Ganesh is a lawyer and writer. He is interested in ancient history and Itihasa and this interest culminated in his first book, "The Pallavas of Kanchipuram: Volume 1", which he co-authored with Mr. K. Ram, a fellow enthusiast of Indian history and culture.

Vignesh Ganesh is a lawyer and writer. He is interested in ancient history and Itihasa and this interest culminated in his first book, "The Pallavas of Kanchipuram: Volume 1", which he co-authored with Mr. K. Ram, a fellow enthusiast of Indian history and culture.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

The Venkateshwara Swami Temple in Tirupati is among the holiest places in the world for Hindus. Millions of people throng the temple every year to get...

It is a sad reality that our Itihasa and Puranas have been subject to severe distortion over the years. This is not surprising considering how even th...

The holy land of Bharat follows Sanatana Dharma. The word Sanatana Dharma is a Sanskrit word meaning, “Eternal law”. It is the indestructible ultimate...